Veteran still deals with impacts of Vietnam War

“I was around 19, taking college classes, when I got mononucleosis. So I dropped out while recovering. And I immediately received a draft notice. I flunked my physical because of the mono, and because one leg was a little shorter than the other. I also had a growth on my throat that they thought might be cancerous. To be honest, I felt relieved. I had no real ambition to go to Vietnam.

“Then, about six weeks later, I got another notice. It was the result of what they called (Defense Secretary Robert) McNamara’s 100,000. They were desperate for more troops, so I got upgraded from 4-F.

“I was stationed in Pleiku, near the Ho Chi Minh Trail, when there was a mortar and rocket attack. We lost some vehicles, so we had to drive down to Cam Ranh Bay to pick up new ones. Along the way, our convoy was ambushed. I was driving, and the guy next to me was shot in the head and killed. It was awful. Something I’ll never forget.

“When we’d go out on patrol, I always told the other guys that if I ever stepped on a land mine and got my leg blown off, make sure you shoot me. Because I didn’t want to live like that.

“I was thankful to God when I finally made it back home. But we lost a lot of good men over there.

“PTSD is real. When I first came back, my wife and I had an apartment about a block away from the fire station in this little town in Ohio. Every night at 10 o’clock, they’d sound this siren that was like a curfew for the kids. I’d roll out of that bed and get underneath. It was like my mind was reacting to a mortar or rocket attack.

“I still have nightmares at times. And if I’m stopped at a railroad track, waiting on the train to pass, I can’t stay in my car. I have to open up the door. It’s like a flashback to that guy getting shot.

“There’s a group of area Vietnam veterans who meet once a week. We get together and talk about anything and everything. It’s just good to know that there are people who went through the same thing you did. Some of them had it a lot worse than me.

Agent Orange strikes

“Physically, I was always into stuff. I played football and ran track in school. I later ran marathons and 10Ks. I also was a soccer referee for years. I was in pretty good shape. But about seven years ago, I began losing feeling in my feet and hands. I’d be driving, and I couldn’t tell if my foot was on the gas or brake. I was diagnosed with peripheral neuropathy.

“When my wife was battling lymphoma [Judy passed away in 2023], other than walking around the hospital I didn’t get much exercise. Then I started noticing my right foot would catch at the ball of my foot, and I’d fall. I couldn’t figure out what was going on. It was drop foot. It’s when your nerve and leg don’t communicate to your ankle to come up, and your foot kind of drags.

“While serving in Vietnam, they sprayed a lot of Agent Orange. When the plane dropped it, it carved a path right through the jungle. We just saw it for what it was. It worked great for the purpose. Years later, as veterans started having all kinds of symptoms, that’s when it really hit home. I had diabetes, neuropathy, some vision loss. Finally, the VA agreed it fell under the criteria for Agent Orange.

“About three months ago, I finally made it to 100% disabled. It took me 14 years to work through the system to get there. I now have total access to anything from the VA. They pay for my prescriptions. They cover medical issues. I get a nice check every month. And there are various other benefits.

“When I get up in the morning, my back aches, my legs ache, and I can’t feel my feet. My fingers don’t work the way they used to. Of course, I’m 78, so that plays into it. But I keep going. I walk at Lee College and I go to Fitness Connection mainly for elliptical and bike. I want to get in better shape so I can travel and see more of the country. I love the outdoors. I’d like to enjoy what time I have left.”

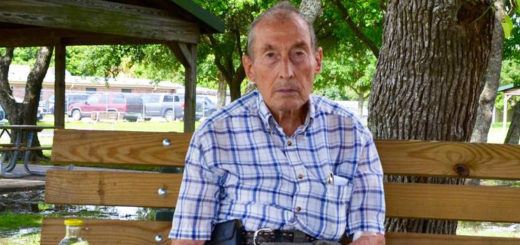

— Gary Gill

Gary was a project engineer for Mobay, Miles and Bayer before retiring in 2008. Mobay in New Martinsville, West Virginia, enabled him to complete his degree in industrial engineering by working and then driving 101 miles each day to classes at Ohio University.